Technology and Vertical Integration

Choosing which activities to engage in, which activities to outsource and which activities to avoid is fundamental for any organisation. From a strategy perspective, this is often thought of in terms of creating a competitive advantage, but economics tends to focus on the minimisation of transaction costs. These perspectives are related, although economics is concerned with efficiency while strategy tries to create excess profits. Technologies that change transaction costs have the potential to reshape the structure and boundaries of industries.

Vertical Integration

Vertical integration refers to the extent to which a firm participates in activities along the value chain within a market. Vertical integration may be pursued in order to lower costs, improve performance or increase control of strategic assets (low-cost resources, customer relationships, distribution channels, patents). Vertical integration also has the potential to reduce uncertainty by increasing the flow of information through an industry’s value chain. The extent to which a market is vertically integrated can fluctuate significantly and is often dependent on the maturity of the industry and the technology it employs.

Figure 1: Illustration of Vertical Integration

The Nature of the Firm

Ronald Coase developed a framework where the vertical and horizontal extent of a firm is determined by the relative cost of employing the market mechanism to conduct transactions versus the cost of hierarchy (substitution at the margin). When the cost of coordinating transactions internally becomes greater than cost of market transactions the firm will stop growing. This can be in reference to:

Growth within a market

Growth across different products

Geographic growth

Vertical integration along an industry’s value chain

Coase came to this viewpoint by considering why there was a need for centrally planned firms, given the problems of centrally planned economies. At a granular level, if all action could be coordinated by the price mechanism there would be no need for the firm at all. Coase realised that there are costs associated with negotiating and concluding separate contracts for each exchange and that in many cases coordinating functions within a firm reduces these costs. A firm is likely to emerge in those cases where a very short term contract would be unsatisfactory, as is often the case for employment.

Uncertainty is also likely a necessary condition for the formation of the firm, as uncertainty increases market transaction costs. In the absence of any uncertainty it would be more practical to negotiate contracts that take into consideration all contingencies (a complete contract). An incomplete contract allows the terms of the contract to be renegotiated in the case of unexpected events. Complete contracts are impossible to execute, while incomplete contracts are expensive.

Transaction Costs

There are a number of different types of transactions costs which relate to the ability to find a suitable counterparty and form an agreement that both parties trust. Transaction costs depend on the environment in which a firm operates, the activities a firm engages in and the technology available.

Figure 2: Example Transaction Costs

As a result of trying to minimise transaction costs firms will tend to be larger when:

The costs of organisation are low and increase slowly as more activities are integrated.

Management is competent and can manage a large organisation effectively.

Activities in a value chain are interdependent as this increases contracting costs, making the market mechanism less feasible.

The legal system is unreliable so that firms can avoid large monitoring and enforcement costs.

Spatial distribution of activities would generally be expected to increase management costs and limit the extent of the firm. In the past this was a more acute problem, but improvements in communication technology have reduced the burden of management from a distance. The relative success of remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic highlights the extent to which technology now enables geographically decentralized coordination of activities.

Vertical integration helps to reduce search, screening and bargaining costs when an organisation is trying to rapidly innovate. This comes at the cost of making the organisation less flexible though, meaning a modular organisational structure may be better for adapting to an unstable environment. A high probability of price changes makes internal management more costly and reduces the potential for integration. This is because markets (short-term contracts) can adjust to price changes more rapidly that central planning (long-term contracts). Transaction variety also leads to higher internal management costs, which should limit horizontal integration more than vertical integration.

Ownership Rights

Integration can also be framed in terms of ownership of rights. Contractual rights can be of two types; specific rights and residual rights. When it is costly to list all specific rights in a contract, it may be optimal to let one party purchase all residual rights (ownership). This may be because they are not verifiable or they are too complex to describe.

A contractual relationship between a separately owned buyer and seller will be plagued by opportunistic and inefficient behaviour in situations in which there are large amounts of surplus to be divided ex-post and in which because of the impossibility of writing a complete contingent contract the ex-ante contract does not specify a clear division of this surplus. Such situations in turn are likely to arise when either the buyer or seller must make investments that have a smaller value in a use outside their own relationship than within the relationship (asset specificities). Through their influence on the distribution of ex-post surplus, ownership rights will affect ex-ante investment decisions. Firms may underinvest if they believe there is a possibility of another party gaining all of the benefits.

From an ownership of rights perspective, residual rights should belong to whoever can manage them most efficiently and the more uncertainty there is the more valuable these rights should be. If variability in the value of residual rights is high across outcomes then integration may make more sense, which suggests vertical integration in the embryonic stages of a new industry.

Figure 3: Illustration of Variability in the Value of Residual Rights

Economies of Scale

Vertical integration can create a number of advantages:

Increased operating leverage due to higher fixed costs

Faster improvement in performance

More difficult to imitate

The integration decision will therefore also depend on whether customers demand lower costs or greater performance and at what scale the firm will be operating.

Figure 4: Vertical Integration and Economies of Scale

Modularity can help realise economies of scale if a particular activity is not primarily related to the industry or if the activity tends to form a natural monopoly. For example, it does not make sense for an auto manufacturer to vertically integrate into the production of steel. Steel is utilised across a broad range of industries and a company focused on steel production will likely operate at a far larger scale than an auto manufacturer focused on producing for their own consumption. This is likely part of the reasoning behind GM’s decision not to vertically integrate into activities that were not primarily related to the automotive industry. At the time this stood in contrast to Ford’s decision to engage in activities like rubber production, coal mining and shipping.

Figure 5: Modularity and Economies of Scale

Industry Maturity

In the early stages of an industry costs are generally high and as a result demand is elastic. Businesses are often well served by pursuing a price leadership strategy as lower prices lead to increased demand and increased industry revenue. Firms can often achieve significant cost declines through experience and economies of scale. These types of gains become increasingly difficult to achieve over time though. As the industry matures, demand will also become satiated. Continuing to pursue a price leadership strategy at this point decreases industry revenue and destroys value. Firms should begin pursuing a differentiation strategy when demand becomes inelastic so that they can continue to increase industry revenue.

While a price leadership strategy may become less attractive as an industry matures, the increase in industry size and complexity makes other options available. Firms can choose to specialize in a particular section of the value chain which may not have provided sufficient scale in the past. There may also be complex steps in the value chain which a specialist firm must focus on to perform adequately. Technology may become so advanced that it is difficult for a vertically integrated firm to remain competitive. This is the situation that Intel now finds itself when competing against modular firms that utilize TSMC for manufacturing.

Firms may also pursue a more modular value chain when they are trying to optimize financial performance in a mature industry. By spinning off low-value add activities and focusing on activities that contribute to their competitive advantage, firms can potentially increase margins and reduce invested capital.

Additional Considerations

In most organizations units are essentially bureaucratic monopolies, which can result in problems like inefficiency, poor quality and a lack of innovation. Opening up internal units to market forces aims to increase competitiveness and improve the interaction of the parts of an organisation through the price mechanism. Internal markets are also a solution to the transfer pricing problems and can help elucidate where value is created within an organisation.

Opening up to market dynamics also creates the opportunity to turn cost centres into profit centres, which potentially maximises the value that a firm can capture. Units with a competitive advantage should not operate as a profit centre though as it will enable external parties to benefit from the competitive advantage. What is optimal for each individual unit may not be best for the corporation as a whole though, meaning the interaction of units also needs to be considered.

Firm’s that make effective use of the market mechanism internally could theoretically extend further either horizontally or vertically by allowing the firm to propagate where the costs of hierarchy are relatively high. If the market mechanism is being effectively used internally the benefits as well as the costs of integration would presumably be reduced though.

Figure 6: Internal Use of the Market Mechanism

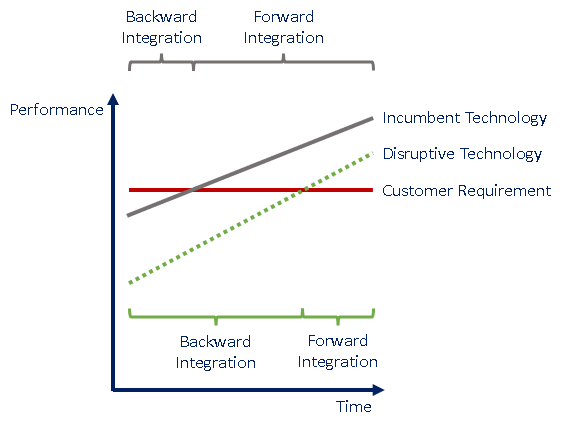

The performance of a technology will generally improve over time as experience accrues and the benefit of investments in R&D are realised. At some point the performance of a technology is likely to exceed the performance requirements of customers. When a product overshoots on performance, flexibility and speed become important. A modular value chain will generally better meet these needs than an integrated value chain. When performance is below customer requirements companies are likely to focus on backwards integration to improve performance and / or lower cost. When performance is above customer requirements companies are likely to focus on forward integration to improve the customer relationship.

Figure 7: Disruptive Innovation and Vertical Integration

Competing firms are likely to try and imitate successful organisations. This should be more difficult when a firms activities are tightly vertically integrated, as imitators have to copy more activities and as these activities are performed internally they are more opaque. Vertical integration therefore has the potential to act as a barrier to entry and a competitive advantage when properly employed.

Technology

The internet is a recent example of a technology that had a large impact on transaction costs and hence greatly reshaped economic activity. Although, the internet should be viewed as part of a broader trend of improving communication and information processing technology. In particular, the internet has given individuals and organisations far greater access to information and hence lowered search and screening costs. This decline in transaction costs created pressure for firms to unbundle activities, which were subsequently rebundled in new forms. This rebundling has often been focused on horizontal integration rather than vertical integration, trying to achieve economies of scale or economies of scope

Airbnb, Uber and peer-to-peer lending platforms are prominent examples of internet enabled businesses that were able to lower search, screening and bargaining costs. These are all generally risky businesses where it can be difficult to match supply with fluctuating demand. Under these conditions, market coordination is optimal as supply can respond more flexibly to demand through the price mechanism.

The reduction in transaction costs has also placed a tremendous strain on many business models that relied on market friction, like intermediaries. Before computers and the internet it would have been a formidable task to try and find the cheapest flight to a destination with multiple route and airline options, now it only takes a few minutes. The impact of this can be seen in things like the decline in trading fees for stock brokers.

A reduction in search and screening costs also made it viable to supply the long-tail of demand in markets like books, music and movies. The long-tail refers to markets where demand is very high for a small number of items and small for a very large number of items. For example, a popular book may sell millions of copies but most books will sell very few copies. In that past it was difficult to supply a large range of relatively unpopular items as there were inventory costs and it was difficult for buyers to find niche items. The internet enabled effective search of massive product libraries and further reduced friction through measures like user reviews and subscriptions. Digital distribution of media also meant that online businesses avoided inventory costs.

Figure 8: Illustration of the Long-Tail of Demand

Conclusion

Vertical integration is often driven by considerations of transaction costs, ownership rights and business strategy. As a result the optimal amount of vertical integration depends on the industry, its maturity and the technology available. In particular, technologies which alter transaction costs significantly have the potential to change the amount of vertical integration along an industry’s value chain. Technologies which change the cost or performance of end products can also impact vertical integration.

Data shows that:

Integration generally improves profit margins but is more capital intensive. As a result integration appears to be a better strategy in less capital intensive industries.

Backward integration generally works better for industrial companies and forward integration generally works better for consumer companies.

Vertical integration generally makes more sense when a company has a relatively large market share, particularly for backward integration.

Vertical integration for the purpose of controlling input costs is generally a poor strategy.

Vertically integrated companies are generally more likely to be responsible for innovations.