Vertical Integration and the Auto Industry

The auto industry has a long history and is illustrative of both evolving customer requirements and technology impacting the extent of vertical integration along the industry’s value chain. Tesla is considered unique for their pursuit of vertical integration but in many ways their strategy echoes Ford’s at the time of the Model T. If the EV market develops in a similar manner to the ICE market, it would be reasonable to expect Tesla to face increasing competition from differentiated rivals in the future. This will likely not occur until the cost of EVs has declined below the cost of ICE vehicles and there is a large supply of Tesla’s available in the second hand market. If this happens, Tesla may need to outsource more of their supply chain, increasing speed and flexibility and enabling an expansion of their product lineup.

Ford

Prior to the mass affordability of the automobile, transportation options included horses, trains and bicycles. Rather than offering a direct replacement for these modes of transportation, the automobile was initially introduced as a luxury item, often custom built for wealthy individuals. These cars were mechanically unreliable, making them more of a novelty leisure item than a means of transportation. The Ford Motor Company began production in 1903, offering a number of models at different price points:

Model A – 850 USD

Model C – 900 USD

Model F - 1,000 USD

Model B - 2,000 USD

Understanding the ability of lower prices to stimulate demand, Henry Ford wanted to introduce a low priced car for the masses, but his partners wanted to focus on higher end models. When Ford took control of the company he dropped the more expensive models and lowered the price of the base models, with the most expensive selling for 750 USD and the cheapest for 600 USD. This led to a dramatic increase in sales, with Ford selling 5 times more cars in 1906 than the previous year. It wasn’t until 1908 when the Ford Motor Company concentrated on a single affordable model that the auto era began in earnest though.

To attain mass market affordability, Ford had to dramatically increase manufacturing productivity. This was achieved based on the principles of specialisation, parallelisation, standardisation, uniformity, interchangeable parts and economies of scale. Ford's original factories did not utilise an assembly line, but stationary manufacturing became problematic at speed as employees wasted time moving around and would get in the way of each other. Ford adopted the assembly line in 1913, which along with improved factory layouts, dramatically improved productivity. As volumes increased the tasks allocated to employees also became increasingly specialised and investments in custom machines became feasible.

Most early auto companies merely assembled components made by parts manufacturers (often legacy manufacturers from the carriage industry). In comparison, Ford aggressively pursued vertical integration in an attempt to minimise costs. Their River Rouge plant was completed in 1928 and was used to assemble cars, smelt steel, produce light and power and make most parts. Ford also owned iron and coal mines, a rubber plantation, a forest, a sawmill, a railroad and steamships.

These types of initiatives led to dramatic improvements in the productivity of labour and reductions in material costs. In 1908 Ford produced approximately 3 vehicles per employee, a figure that rose to almost 6 in 1911. By 1914 Ford were producing 20 vehicles per employee, compared to only approximately 0.66 by the Packard Motor Company. In 1909 assembly of a Model T took 12 hours, by 1914 it took only 93 minutes. Between 1909 and 1917 the value of PP&E at Ford doubled to 1,606 USD per employee. The cost of materials (raw materials and manufactured parts) per Model T dropped from 590 USD to 262 USD between 1909 and 1916. Wages were more constant at around 64-70 USD per vehicle, at least partly indicating the extent to which Ford was willing to pass the benefit of productivity gains through to employees in the form of higher wages.

Demand stimulated by lower prices, and lower costs as the result of increased production volumes, created a powerful feedback loop until the price elasticity of demand of the Model T began approaching 1 in the early 1920s. As the car industry matured, the market for used cars also developed, creating a secondary threat to Ford’s cost leadership strategy. In 1920 used cars accounted for 38% of all cars sold, a figure that had risen to over half by 1927.

While the Model T was a reliable and affordable vehicle, it left much to be desired and by the 1920s was becoming insufficient for a large portion of the market. General Motors recognised that many consumers were willing and able to pay slightly more to address issues like:

Lack of power

Vibrations and road noise

Poor handling and braking

Gears that required skill to change without clashing

General Motors gained market share in the 1920s by manufacturing better quality vehicles at higher price points, ushering in a period of mass market adoption served by increasing quality. The combination of competition from used Model Ts, and better quality vehicles from General Motors, squeezed Ford from above and below. In 1927 Ford was forced to completely close the River Rouge plant for almost a year in order to retool, so that more competitive models could be introduced. Ford regained sales leadership in 1929, but had squandered their once dominant position in the industry.

Figure 1: Model T Sales Price and Annual Production

General Motors

General Motors was formed by William Durant (no relation that I’m aware of) in 1908. Durant recognised the potential of the automobile market early on and began building a portfolio of brands through acquisitions. Between 1908 and 1910, General Motors acquired approximately 25 companies (11 autos, 2 electric lamp producers and the remainder were parts and accessories companies). General Motors did not have a clear strategy though and struggled with high costs and mediocre sales, with brands often competing directly against each other. When Alfred Sloan was given control of operations in 1920 he reorganised GM so that the company was coordinated in policy and decentralized in administration, with the correct financial incentives. Through this arrangement, General Motors aimed to realise economies of scale while maintaining differentiation. Sloan also rationalised the portfolio of brands so that each was competing for a separate market segment. General Motors’ strategy was formulated on the assumption that living standards would rise significantly, leading to increased consumer purchasing power and demand for more expensive autos. Under Sloan the initial lineup of cars was offered in 6 price bands:

Band 1 – 450-600 USD

Band 2 – 600-900 USD

Band 3 – 900-1,200 USD

Band 4 – 1,200-1,700 USD

Band 5 – 1,700-2,500 USD

Band 6 – 2,500-3,500 USD

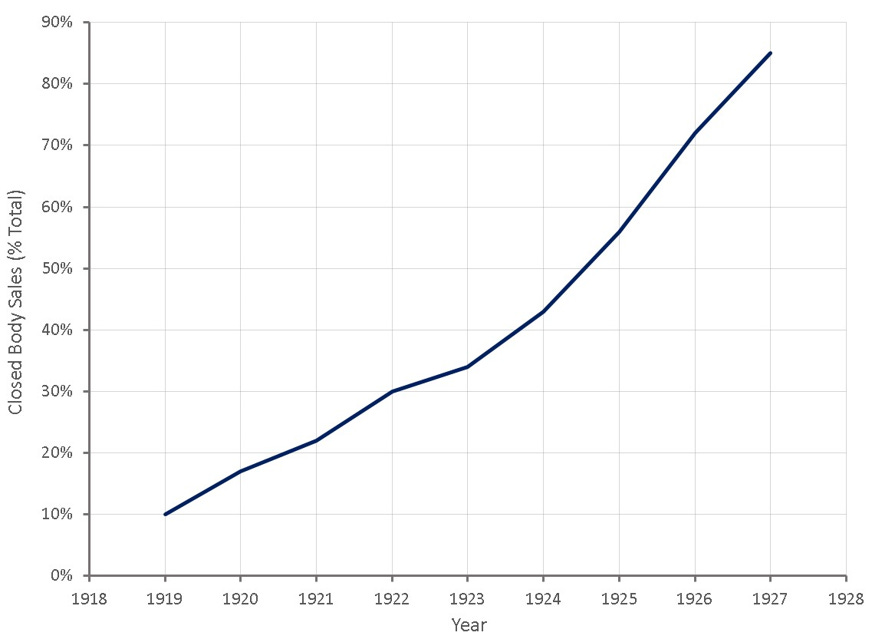

General Motors introduced features like the closed body, power steering, power brakes, air conditioning and synchromesh and automatic transmissions, which more than justified the higher price points and led to market share gains.

Figure 2: Closed Body Vehicle Sales (% Total)

Along with additional features, General Motors introduced the concept of the annual model update, which helped shift the basis of competition towards speed and flexibility. These were areas that Ford struggled to compete in due to past over optimisation for low-costs. By the middle of the century, many households could afford more than one vehicle and General Motors helped to stimulate demand by introducing a range of vehicle types:

Sports cars

Station wagons

Hardtops

Pick-up trucks

Figure 3: Cost Leadership versus Differentiation

General Motors was far less vertically integrated than Ford, although made more of an effort to foster customer relationships. Sloan recognised that it made little sense to participate in activities like mining that were not primarily related to the auto industry. Specialised firms could operate in these areas at much greater scale and hence more efficiently.

Auto manufacturers generally have limited relationships with end customers, as car sales are a hard activity for large corporations to manage effectively. Dealers are generally involved in trade-ins rather than ordinary sales, which makes it a difficult activity for manufacturers to integrate. While General Motors and Ford have both outsourced the distribution of vehicles, General Motors historically had a much better relationship with their dealers and made more of an effort to ensure their success. The General Motors Acceptance Corporation was formed between 1918 and 1920 and provided financing to dealers and customers. Financing was part of General Motors’ strategy to stimulate demand for higher priced vehicles. In addition to financing, General Motors offered insurance and had a greater focus on advertising than Ford. These efforts brought General Motors closer to customers than Ford had been, an important consideration given their differentiation strategy.

The Japanese Manufacturers

In the 1970s and 1980s, cars manufactured in the US suffered from poor quality, opening the door to foreign competitors. The 1970s oil crisis also increased demand for smaller vehicles. Japanese manufacturers were able to capitalise on this situation with their affordable and reliable compact cars.

Relative to the US, Japan lacked access to capital and had lower labour costs, leading to more labour intensive manufacturing methods. Japan's market was also smaller and more differentiated, leading to a premium on model variety and smaller production runs. This led to Japanese manufacturers utilising more flexible manufacturing methods, with a focus on continuous improvement. Design for manufacturing also led to greater productivity. In particular, Toyota was known to spend more time on planning, so that implementation occurred faster and as a result was quicker from design to production.

Toyota also placed an emphasis on minimising inventory and waited until products were pulled from manufacturing by demand rather than pushing supply onto the market. Toyota developed a sophisticated supplier network to avoid extensive stockpiling and often worked closely with suppliers to help them eliminate waste. Tighter integration between suppliers and manufacturers led to an increase in the capabilities of suppliers, many of whom advanced to the supply of sub-assemblies rather than just parts. This shift eventually made it feasible for new companies like Tesla to enter the industry with an asset light approach. US manufacturers were forced to adopt lean manufacturing methods to remain competitive, but the results were mixed. General Motors’ multi-division structure hampered a shift to lean manufacturing, as the same lessons had to be applied within each division.

Tesla

Tesla was founded in the early 2000s, gaining a foothold in the auto industry by capturing the opportunity afforded by lithium ion batteries. Tesla started by converting imported British sports cars to electric drive, at a time when other EV manufacturers were focused on the low-end of the market. Tesla's business plan from day one was to build high-end sports cars and then move down market as their costs declined, honing their capabilities on small volumes before scaling up. This was a prudent approach as large scale production with inefficient processes could have been fatal for a company with limited financing.

Tesla is vertically integrated to drive innovation and lower production costs. This includes integrating into the production of solar panels and batteries for energy storage. While this may be necessary to drive scale for battery production, if the EV market fragments significantly this level of integration could become a serious burden. Tesla is also vertically integrated in their efforts to develop autonomous vehicles, which has even extended to designing their own processing units.

Tesla has introduced a number of unique elements into their business model, which differentiate them from legacy manufacturers. Tesla do not utilise dealers and they perform their own servicing. This improves margins and strengthens their relationship with customers, but may become problematic as the supply of used cars increases. Tesla also provide over the air software updates, insurance, financing and a supercharger network, all of which reinforce the customer relationship.

In addition to increased competition from legacy manufacturers switching focus to EVs, Tesla will also begin to compete with their own vehicles in coming years. The average length of vehicle ownership is approximately 7 years, which implies a large supply of used Tesla’s will be available around 2024. Tesla isn’t aimed at the low-end of the market like the Model T though, so this should be less of an issue. Greater model variety may be required once there is a large supply of used Tesla’s available, and it will also likely create pressure to introduce significant annual model updates.

Figure 4: Tesla Unit Sales

The Ebb and Flow of Integration

Ford started out with a modular value chain, primarily performing assembly, with the supply of parts outsourced to vendors. In time, Ford became extremely vertically integrated in the pursuit of lower costs. Ford made little effort to develop relationships with customers though, instead utilising a distributor network which they had a fairly antagonistic relationship with. As the industry matured, the benefits of integration waned and in some cases suppliers could achieve greater economies of scale. After Ford lost its dominant market share, the benefits of integration were further diminished and may have even become a burden.

Once the auto industry had matured, innovation was relatively low, making modularity more feasible (less uncertainty and less need for innovation). An increased focus on differentiation and annual model updates also necessitated the flexibility and speed enabled by modularity. Over time the industry value chain became more modular as scale increased and vehicles became more complex. Japanese manufacturers in particular had close relationships with suppliers and increased their involvement in design and the supply of sub-assemblies.

The auto industry’s relatively modular value chain in the early 2000s, opened the door to new entrants, when battery technology reached a point that EVs were commercially viable. Tesla initially relied on a modular value chain, primarily acting as an assembler, mirroring Ford a century earlier. As their business has scaled, Tesla has become increasingly vertically integrated to lower costs and drive product improvements.

Figure 5: Evolution of Auto Industry Value Chain

Fascinating! Will check out your other posts and thanks for the excellent work on Amyris on Seeking Alpha. Really enjoy your thoughtful work.