The Societal Impact of The Singularity

The Singularity has the potential to raise living standards but it could also cause rising inequality, social unrest and a change in governmental institutions.

If The Singularity were to occur it would raise living standards significantly, but could also cause problems like rising inequality and social upheaval, which may negate many of the benefits. Critical focus on The Singularity often discusses the existential threat of sentient AI, with little consideration given to more basic issues like how society is governed and how resources are allocated.

Negative Side Effects of The Singularity

If technology continues to advance in coming decades, particularly in AI and robotics, it will likely lead to capital substituting for labour on a wide scale. While some workers who are assisted by these technologies will benefit significantly, many if not most, could suffer unless new employment opportunities are created. If AI and robotics become sufficiently advanced it is not clear this will be the case though, setting the stage for rising inequality and with it, the risk of social unrest. Other potential issues include:

Inability of people to support themselves without employment opportunities

Lack of purpose without employment opportunities

Declining incentives to pursue education

Inability of developing countries to close the wealth gap with developed countries

Dangers of Social Upheaval

A lack of employment opportunities and rising inequality may require the fundamental tenets of society be reconsidered, creating the risk of social structures that are worse for the average person. The two most comparable periods in human history are the agricultural and Industrial Revolutions, both of which saw dramatic changes in the modes of production, rapid productivity gains and a restructuring of society.

For example, while the Industrial Revolution may not have been the proximate cause, in the years during and since there was political turmoil and some of the worst events in human history:

American Revolutionary War (1775-1783)

French Revolution (1789-1799)

American Civil War (1861-1865)

World War I (1914-1918)

End of the Russian Monarchy (1917)

End of the Habsburg Monarchy (1918)

Russian Revolution (1917-1923)

World War II (1939-1945)

Chinese Communist Revolution (1945-1950)

Peter Turchin has done extensive research on how structural demographic, social and political factors have historically oscillated, leading to periods of unrest. A breakdown of central authority, fighting among political groups and a general increase in violence can result when:

There is an excess of elites who try to extract more from society to maintain their standard of living.

Elites try to prevent upward social mobility for commoners so there is less intra-elite competition.

Elites resist taxation of income and profits to maintain their standard of living.

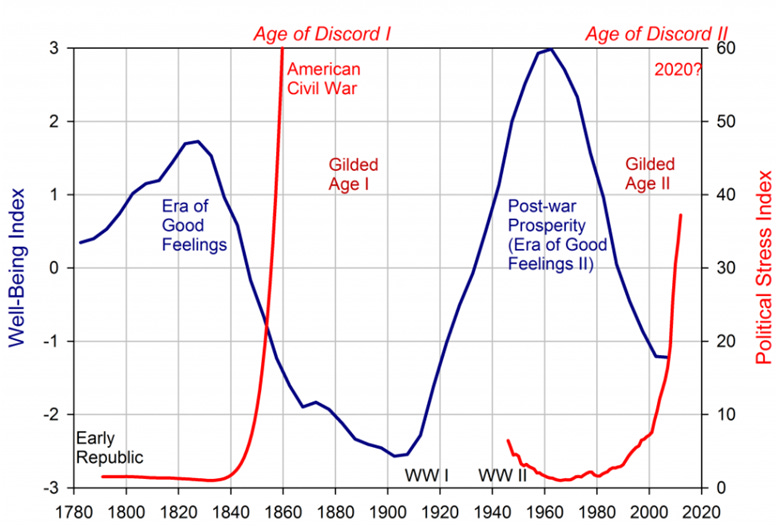

If the state cannot provide sufficient protection to the populace it affects the productivity of society and a collapse can occur, leading to fragmentation which may not be built up again into a functioning state. Turchin has long been forecasting a period of growing instability in the United States and Western Europe based on a number of indicators related to inequality, well-being and social cohesion.

Figure 1: Well-Being and Political Stress in the U.S. (source: NOEMA)

The Agricultural Revolution

The agricultural revolution is the name given to a number of cultural transformations that allowed humans to transition from hunting and gathering to agriculture approximately 12,000 years ago. It has been hypothesized that hunter-gatherers began farming due to its superior labour productivity. While farming undoubtedly raised the productivity of land, some archaeologists doubt that it increased the productivity of labor, at least not for many centuries. Societies with possession-based private property may have preferred farming as it allowed private possession to be more readily established and defended. In this manner, agricultural societies could have been established without a productivity advantage.

Because agriculture no longer required migration in search of food, humans were able to establish permanent communities, which in turn caused rapid increases in population density and the emergence of civilization. Agriculture provided a relatively safe existence and arguably more leisure time for creative pursuits, resulting in the accelerated evolution of art, religion and science. It also triggered various other innovations including new tools, commerce, architecture, an intensified division of labour, defined socioeconomic roles, property ownership and tiered political systems. The agricultural revolution was not all positive though, as productivity gains generally increased populations without improving living standards. Increases in population density also correlated with an increased prevalence of diseases and interpersonal conflicts and extreme social stratification.

The Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was a complex historical process that combined economic, social, cultural and scientific forces. It was driven by the introduction of new technologies, between 1760 and 1840, including chemical manufacturing and iron production processes, steam and water power, machine tools and the mechanized factory system.

The Industrial Revolution increased productivity, but it also created hardship for many in the short-term, before gains became more wide-spread. In the period between 1780 and 1840, output per worker in the UK grew by 46%, but real weekly wages only rose 12%. The profit rate doubled during this period and the share of profits in national income expanded at the expense of labour and land. It is possible that this surge in inequality was intrinsic to the growth process, as initial technological progress increased the demand for capital and raised the profit rate and capital’s share of income. The rise in profits in turn, sustained the Industrial Revolution by financing the necessary capital accumulation. After the middle of the 19th century, capital accumulation had caught up with the requirements of technology and wages rose in line with productivity.

Similar to the agricultural revolution, the Industrial Revolution also led to an unprecedented rise in population growth. There was a large amount of migration during this period, as people moved from subsistence farming in rural villages to the industrial economy in urban cities. Living conditions were poor for the working class and the newly concentrated population increased awareness of their struggles. The Industrial Revolution prompted the formation of trade unions and discussions about minimum wage laws and a form of universal basic income, which caused concerns about how markets would be distorted and the supply of labour reduced. Over 150 years later, these discussions about inequality and how it can be reduced are still ongoing.

The fact that technological progress did not initially improve living standards for the majority was foundational to the radical politics of the era. The Industrial Revolution led to a more participatory society with rights for the general populace greatly expanded. Voting rights were widely expanded in in the UK in 1832 and universal suffrage was achieved in 1928.

At the start of the Industrial Revolution taxation in the UK was very low by modern standards and had no substantial redistributive consequences. Government was focused on administration rather than legislation and nothing had yet been done about health, education or poverty at a national level. Government expenditure mainly took the form of military and crown expenses.

At the start of the Industrial Revolution the state owned neither the means of production nor infrastructure but over time increasingly took responsibility for the control of private enterprise in the interest of society as a whole. While industry overall was in private hands during the Industrial Revolution, infrastructure and utilities were not purely in private hands. The state not only authorised and shaped undertakings in these fields, but in some cases also retained a degree of control over them.

Inequality

The agricultural and Industrial Revolutions created the potential for greater inequality due to the increase in productivity and the resulting rise in income. Despite this, inequality levels in most societies has not exceeded a Gini coefficient of approximately 65. This may be because the majority of people view society as too extractive at this point, causing a breakdown. Income inequality was high prior to and during the Industrial Revolution, before declining significantly between 1900 and 1980. Inequality has risen in a number of countries over the past 40 years though, particularly those that have not aggressively pursued redistributive policies.

Table 1: UK Income Inequality (source: ourworldindata)

Rising inequality is also at least in part due to technology eroding the base of middle income jobs. In recent years the labour market has become increasingly polarized and job growth is now driven primarily by high and low skill jobs. Wage increases are also primarily accruing to high and low skill jobs, with relatively weak wage growth for the jobs in between.

Figure 2: Employment and Wages by Skill Percentile (source: MIT Technology Review)

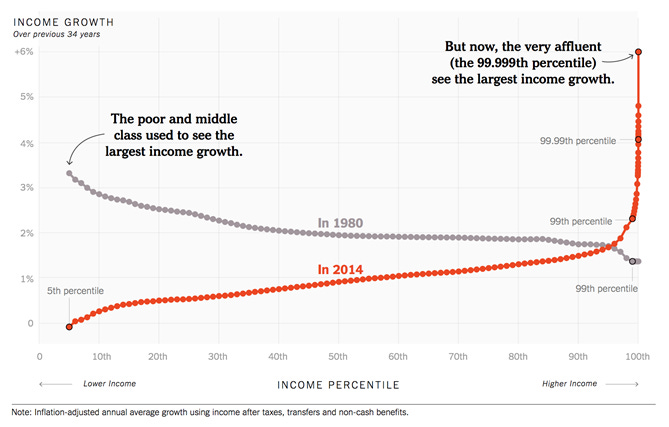

Income growth is currently far higher for high income individuals in the US. This is opposite to the situation in 1980, where income growth was high for low income individuals. If this situation persists it will lead to greater inequality and increase the possibility of social unrest.

Figure 3: Income Growth by Percentile 1980 and 2014 (source: ourworldindata)

Global trade, government policy, financial crises and technology have all been suggested as possible explanations for rising inequality. It is also possible that this situation is the temporary result of a weak labour market with relatively low participation rates and high unemployment. The labour market in the US appeared to be strengthening prior to the pandemic though, leading to rising household incomes. If this situation persists after the pandemic, it could begin to reverse the rise in inequality.

Figure 4: US GDP per Capita and Household Income (source: The Federal Reserve)

Economics of Marx’s Socialism

Karl Marx developed a theory about how capitalism would inevitably evolve into communism based on his observations of the Industrial Revolution. Marx thought that capitalism had an inherent tendency towards crises, which would become worse over time. He believed this was due to difficulty in predicting demand, leading to over production in some areas and under production in others. Marx argued against the under-consumptionist theory of crises, although with a lack of employment opportunities, this may become valid in the future. Marx also assumed that profits cannot be profitably reinvested into productive activities, consequently leading to declining returns on capital. The combination of declining returns and worsening crises would cause ownership of the means of production to become increasingly concentrated over time. A growing class of workers exploited by a shrinking class of capitalists would inevitably result in a revolution and a socialist state where the means of production are communally owned would be the end result. Marx recognized that capitalism increased living standards, but was more concerned with relative living standards than absolute quality of life. He focused on a society that sought for its members the development and exercise of their physical and mental faculties rather than higher living standards.

Marx provided little detail on what such a socialist utopia would look like and what has so far been put into practice has been indefensible. Some of the assumptions made in Marx’s theories also have fundamental limitations and have not held up as society evolved. For example, it was assumed that capital did not contribute to production and therefore should receive minimal compensation, it was also believed that the actions of the manager / entrepreneur contributed little and therefore did not deserve compensation either. Marx’s predictions have deviated from real data in part because of the limitations of such assumptions, but also because capitalist societies adapted so that gains were more evenly distributed.

While The Singularity could be considered a catalyst for a socialist revolution, there are a number of issues. In the event of The Singularity there would be no labour to exploit and there is no reason to think that more crises would occur or that returns on capital would decrease.

Universal Basic Income

Universal Basic Income (UBI) is one commonly proposed solution to widespread structural unemployment as a result of The Singularity. In the event of a true technological singularity where there is little need for anyone to work, it is likely that there would be little resistance to UBI and few problems caused by implementing one. Prior to this though, those who pay a large amount of tax to support UBI may feel exploited and UBI may discourage people from pursuing productive activities, particularly if the income level is set too high. From a moral perspective it raises questions about identity, purpose and value that many people experience as a result of work. From a societal perspective, there are huge second-order questions too, for example would schools continue to exist if people have no economic function and no need to worry about employment.

The cost of providing even a subsistence level of income currently appears prohibitive, but in the event of The Singularity would likely readily become manageable. In addition to the high cost of implementing UBI, there is the potential issue of making a large group of people dependent on the government. For this reason it may be preferable to have UBI administered outside of government control or to ensure distributed ownership of societies resources instead. This is similar to the objectives pursued by initiatives like mandatory superannuation and sovereign wealth funds.

Table 2: Feasibility of UBI in the U.S.

Reduced Working Hours

If technology does cause structural unemployment, a primary course of action would presumably be to reduce the amount employed people work. Rather than having a relatively small number of full-time employees and a large group of unemployed people, it may be preferable to transition towards less working hours for everyone, with these working hours more evenly distributed. For example, rather than working 40+ hour weeks for 46-50 weeks a year, in the future people could work 20 hour weeks for 26 weeks a year. People may also choose to retire significantly earlier. A combination of these factors could lead to an 8 fold reduction in the number of hours worked by an individual over a lifetime, allowing significant substitution of capital for labour in the workforce without widespread unemployment. This would delay the need for UBI and help to ensure that as many people as possible remain productive members of society.

This has historical precedence, with the number of hours worked falling sharply between the 1880s and 1920s. This was due to a combination of shorter work days, shorter work weeks and an increase in vacations, holidays, sick days, personal leave, and earlier retirement. The trend towards less working hours began to flatline around 1970 in a number of countries though.

Figure 5: Annual Hours per Worker (source: ourworldindata)

There are a number of potential barriers to reducing working hours significantly from current levels though, including:

Demand - Many people may wish to continue working long hours, even if they are earning a relatively high income, due to a desire for increased consumption.

Cultural - Hard work is considered a positive personal attribute in many cultures, which may lead to a reduction in work hours being viewed negatively.

Coordination - While there is evidence that part-time employees are more productive, there could be difficulties coordinating between employees who are absent from work for significant periods of time.

Global data indicates that as GDP per capita rises there is a tendency for the number of hours worked to decline. This reduction in hours appears to be more dramatic at lower levels of GDP per hour, implying that extremely large gains in productivity will be needed in the future to drive a significant reduction in hours worked.

Figure 6: GDP per Hour and Annual Hours per Worker (source: ourworldindata)

It may already make sense to push for less working hours due to the fact that labour force participation rates have been relatively low and unemployment rates have often been relatively high in recent years. The 40-hour work week is also inconsistent with a number of ongoing trends, including the shift towards project and team-based work, the rise of the gig economy and the globalisation of tasks and teams

Conclusion

The Singularity or an acceleration of technology driven innovation could raise living standards, but these gains are unlikely to be evenly shared. Inequality can foster social unrest, making this an important concern that will need to be addressed. This may require a redistributive policy like UBI or a mechanism to ensure widespread ownership of societies resources. Governance institutions may also need to evolve to meet the needs of a rapidly developing society. The ability of all of this to occur without violence or the implementation of a totalitarian government should be a prime concern for society.